More than half a million trod here; for the city that hosted the largest forced population transfer in human history, it’s never too late to remember

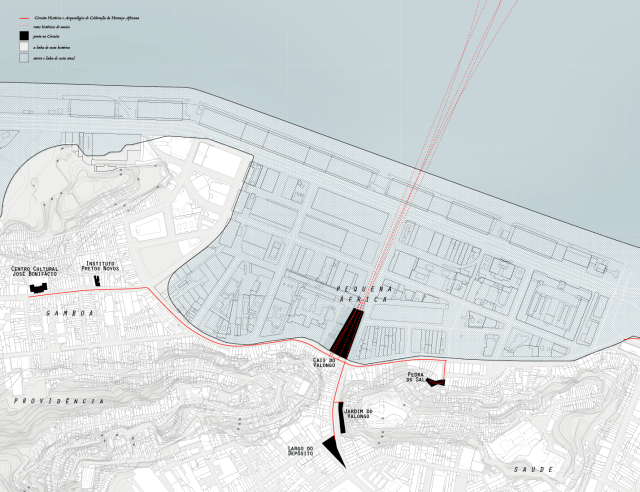

Visitors will be able to get a sense of the tragic path of slaves arriving in Rio de Janeiro (map by Sara Zewde)

The Rio de Janeiro city government, together with neighborhood associations and groups involved with the Afro-Brazilian legacy, is upgrading an existing visitor circuit, that could ultimately stand out among all other locations in the world reminding us of one of the biggest tragedies of human history.

Para Memorial da escravidão fará parte do Porto Maravilha, clique aqui

In Washington D.C. the United States is building the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the Brazilian federal government has similar plans. São Paulo boasts its excellent MuseuAfroBrasil, which even offers virtual visits. The United Nations will build a monument to memorialize Transatlantic slavery, which involved 15 million human beings. Philadelphia already has a memorial, which reminds visitors that two slave-owning American presidents lived in a house located there.

Rio de Janeiro’s project, says Rio World Heritage Institute president Washington Fajardo, will be almost complete by the opening of the 2016 Olympic Games — and will be quite different from any other memorial for this dark historic period.

Rio has good reason to innovate.

At the height of slavery, several years after the 1808 arrival of the Portuguese court as it fled Napoleon, more than half a million Africans passed through the Valongo area, disembarking from slave ships. Now, the region could become a unique point of reference, both for local residents and visitors from outside the metropolitan region.

The Circuito Histórico e Arqueológico de Celebração da Herança Africana (Historic and Archeological Circuit Celebrating the African Legacy) will include the recently-discovered Cais do Valongo (Valongo Wharf), the Instituto dos Pretos Novos (New Blacks’ Institute, final resting place of slaves who died on the journey or shortly after arrival), the recently-restored Jardim do Valongo (Valongo Gardens), the José Bonifácio Cultural Center, the Pedra do Sal (Salt Stone, now an outdoor samba venue, at the foot of the rock where slaves unloaded salt) and the Largo do Depósito (Warehouse Place), where slaves were fattened and sold. The circuit will also include the Docas Dom Pedro II warehouse (which now houses the Comitê Ação da Cidadania or Citizenship Action Committee), built by the black abolitionist André Rebouças in 1871 – without slave labor, as he had ordered.

Fajardo told RioRealblog that City Hall is focusing above all on the circuit’s sustainability. The Institute is working with neighborhood partners — brought together for this purpose in the Curating Work Group for the Urban, Architectural and Museological Circuit Project. The group prepared a recommendations document, parts of which have been incorporated.

The Circuit will feature a bold memorial that Sara Zewde, a Harvard University landscape architecture masters’ student, helped to research and create. Instead of a statue, monument, building or wall, the memorial will be the public space between the Wharf, the Valongo Gardens and the Warehouse. The current plan is for this space to encourage visitors to sit, walk and reflect, among trees, shade and light.

“This is a world, and the way it operated, for a long time,” says Sara.

Slavery ended almost 127 years ago. But the Valongo Wharf, where slaves landed from 1811 to 1831, reappeared — with two superimposed anchorages — only in 2011, during the Porto Maravilha port revitalization excavations. These also revealed a large quantity of slave belongings, such as amulets.

Remodeled in 1843 so that the Princess María Mercedes of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, Teresa Cristina Maria de Bourbon, fiancée of (then) future Emperor Dom Pedro II, could disembark in comfort in Rio de Janeiro, the Wharf was buried in 1911. And then, forgotten.

Today, the location – part of a region whose history is at the core of Brazil’s African heritage — has the eye not only of City Hall and Afro-Brazilian leaders, but also draws attention from the United Nations.

In 2013, the Wharf was named part of the city’s cultural heritage. The following year, the city began to develop its candidacy for selection as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. UNESCO, the U.N.’s culture and education arm, will announce its decision in the first quarter of 2016.

The memorial will break with Western practice regarding public space, attempting instead to echo the traditions of enslaved Africans’ native lands, says Sara Zewde. The biggest challenge will be to help visitors gain a sense of the connection between past and future, a strong element in many African cultures.

Circular forms and musical rhythms seen today in samba circles, Candomblé religious rituals, Afoxé traditions and the capoeira dance/martial art, will be part of the memorial, whose visual identity will be selected in a contest to be held this year.

In addition, Sara notes, the memorial will underscore the connections between the African continent and Brasil, using water and trees – and maybe even a baobab — that slaves would have known in their native lands. She also hopes to recreate the sad passage that slaves trod on landing in Rio, as best as can be done, given the amount of landfill that took place over time. According to her, the Circuit’s paving material will contain information about the trees.

“In [the] Candomblé [religion]” says Sara, “The universe is a tree.”

To learn more, in Portuguese: http://guiadoestudante.abril.com.br/aventuras-historia/saiba-tudo-cais-valongo-local-onde-entravam-africanos-escravos-brasil-seculo-xix-731373.shtml

All very well. But I get so tired of people saying, “Slavery was terrible. I’m glad we don’t have such things today.” Slavery is gone but human nature cannot change in 200 years. The aspects of human nature that made slavery possible are still with us. The tendency of humans to exploit other humans is still with us. Exploitation is still with us. We must remember also that humans have a tendency to resist exploitation, when they can, and humans do have a sense of right and wrong, when it is aroused. Those are the main reasons we don’t have slavery today. (Along with differing material conditions.)

By the way Julia, the meaning of the word “circuit” is perfectly clear but I wonder if there is a differ English word for it. Thanks for an interesting article.