We’ll be able to know so much

Brazil has a long tradition of mystery, when it comes to public safety. Sometimes, neither the actual public policy nor its exact targets are known — currently the case in Rio de Janeiro (also on the national level). Sometimes management details aren’t publicly available, as occurred during the Federal Intervention last year and later, with current governor Wilson Witzel’s decision to abolish the Public Safety Secretariat. We also have no information on the real cost of the pacification program, implemented in Rio during José Mariano Beltrame’s term as state Public Safety Secretary.

Para português

The crime data itself can be surprising: contrary to what one would expect, national crime data is not the federal government’s responsibility. Instead Brazil turns to a not-for-profit organization, supported by foundations, multilateral organizations and NGOs, the Forum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública (Brazilian Public Safety Forum).

And now we’ve got a new mystery: how and why are crime numbers falling in Rio state? Should we assign kudos to greater police violence and governor Witzel’s support for police operations in the metropolitan region’s favelas? It’s easy to think that more police bullets lead to fewer robberies and other crimes.

State legislators Renata Souza e Mônica Francisco, elected in 2018 for the PSOL party, support the network

Starting June 1, the Centro de Estudos de Segurança e Cidadania (Center for Security and Citizenship Studies), CESeC, will provide us with more transparency. CESeC is launching a network to collect data and exchange information, the Rede de Observatórios da Segurança Pública (Public Safety Observatories Network). Composed of organizations in the states of Ceará, Bahia, Pernambuco, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, the network is supported by the Ford Foundation, the Open Society Foundations and the Cândido Mendes University.

From now until April 2021, the Network plans to provide solid resistance to police violence, which is growing across the country. It will provoke thinking, debates and action to draft public policy aimed at crime and violence reduction. The objective is to go beyond official numbers, documenting general policing, state agent victimization, police corruption, mass killings, the juvenile and penitentiary systems, lynchings, armed violence, actions and attacks by criminal groups, demonstrations, strikes and protests, state agents’ abuses, feminicide and other violence against women, racism and racial offenses, violence against LGBTQ+, religious intolerance and violence against children and teens.

Ironically, one area that holds zero mystery is our knowledge of effective public policies. In 2017, for example, the Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (Applied Economic Research Institute, Ipea by the Brazilian acryonym), a federal body, published the thinking of some of the most prominent public safety actors and researchers, on what the federal government’s role ought to encompass. For various reasons that have little to do with citizens’ needs, government officials discard such recommendations based on reality, facts and numbers.

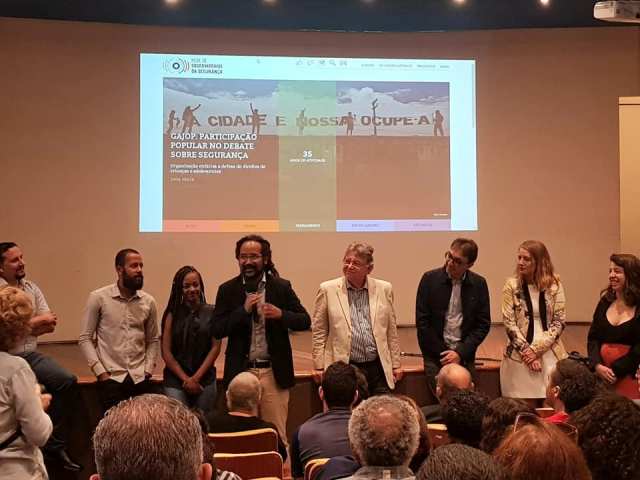

This week’s launch of the Network filled the National History Museum’s auditorium with public safety activists, actors and researchers. Called to the microphone, many of these told of the shock they feel as they witness government and society’s support for more violence in Brazil’s streets and jails.

Átila Roque, the Ford Foundation’s Brazil director, said he identifies a political project for the use of violence to “regulate order, supress revolt.” Monica Francisco, elected state representative last year for the PSOL party, part of what she called the “quilombo (term for formerly enslaved people’s refuges, referring now to Afro-Brazilian politicians) caucus”, said that just a few years ago she couldn’t imagine today’s increasing [police and army] impunity for the deaths of favela residents , much less last year’s murder of city councilwoman Marielle Franco (together with her driver), with whom she worked.

Retired Colonel Íbis Pereira, former Military Police commander (2014), wept as he tried to describe the current situation. Itamar Silva, Instituto Brasileiro de Análises Sociais e Econômicas (Brazilian Institute for Social and Economic Analyses, Ibase by the Brazilian acronym) and Santa Marta favela resident, avoided lamenting the present, celebrating last year’s election of several legislators from favelas and other peripheral areas. He criticized the left for having ignored public safety concerns while in power.

Until we have more information, specialists say, we hone our critical thinking. Pablo Nunes, Network researcher and coordinator, told RioRealblog that today’s drop in Rio state crime rates may turn out to be similar to what happened during last year’s Federal Intervention: cargo theft dropped only while police and army soldiers clamped down on it. Joana Monteiro, formerly in charge of Rio state crime statistics and now coordinating a data research center at the state attorney general’s office, notes that the Military Police have more functioning automobiles this year, than last.

Nunes expects crime to make a comeback; he says that what is needed, in addition to a healthy police street presence, are intelligence on the dynamics at work and crime case solutions.

This is a lesson learned before, in the 1990s and 2000s.

Nunes also points out that lethality is still high when police-caused deaths (which are rising) are tallied along with other homicides. He believes that current police behavior is unsustainable. There are no official violence reduction targets.

“The Witzel administration has put forth very little in regard to a public safety policy,” Nunes adds. “They haven’t even presented a project draft, all they have are slogans, they say the police should go and take care of business, but we have yet to see a framework for what the Military Police are supposed to do, what the Civil Police are supposed to do, or for any other public safety actors. What we’ve seen is each one acting on its own.”